Addressing access to care

in rural areas

Dr. Tina Woods grew up on Saint Paul Island, a remote speck in the Bering Sea, 750 miles west of Anchorage.

There is only one school, one post office, one church, one bar and one small store on the island. Access to healthcare has always proven difficult.

Dr. Woods, who has a degree in clinical community psychology with a rural indigenous emphasis from the University of Alaska, has devoted her career to improving access to care in rural areas. She works in collaboration with rural and remote communities through the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, a nonprofit Tribal Health entity that works to support the health care needs of Alaska Native and American Indian people.

"Promoting health equity across the lifespan is important for every human being, no matter who you are or where you live," Dr. Woods said. "Here in Alaska, we have to be really creative with health care solutions that meet the needs of our people, like for my people in in my hometown."

As the United States grapples with the high cost of medical care and debates how to improve the healthcare system for all, one challenge that often gets less attention is the significant disparity between urban and rural healthcare. In this country, people living in rural areas suffer worse health outcomes than their urban counterparts. They're sicker, poorer and older and are more likely to experience higher rates of death, disability, and chronic disease.

"These small communities tend to be forgotten," said Jac Davies, executive director of The Northwest Rural Health Network, a nonprofit network of 15 rural health systems in Eastern Washington.

Saint Paul Island has a population of about 500, which increases to about 700 during the summer halibut fishing season. The only way off of this 7.5-miles wide by 13.5 miles long Pribilof island is by air, with planes leaving the island three times a week. Roundtrip airfare to Anchorage is $1,300.

The island is served by a community health center, which is staffed by a health aide and likely a nurse practitioner or physician assistant. Specialists come in when available. There is no hospital on the island, so patients who need hospital care must fly to Anchorage. This includes flying out for cancer treatments, surgery and even childbirth. Women having babies in rural Alaska must fly to a city with a hospital at least one month before their scheduled due date, stay in a hotel or other overnight facility—often alone and separated from family—until they give birth and the baby is ready to fly back to their remote town or village.

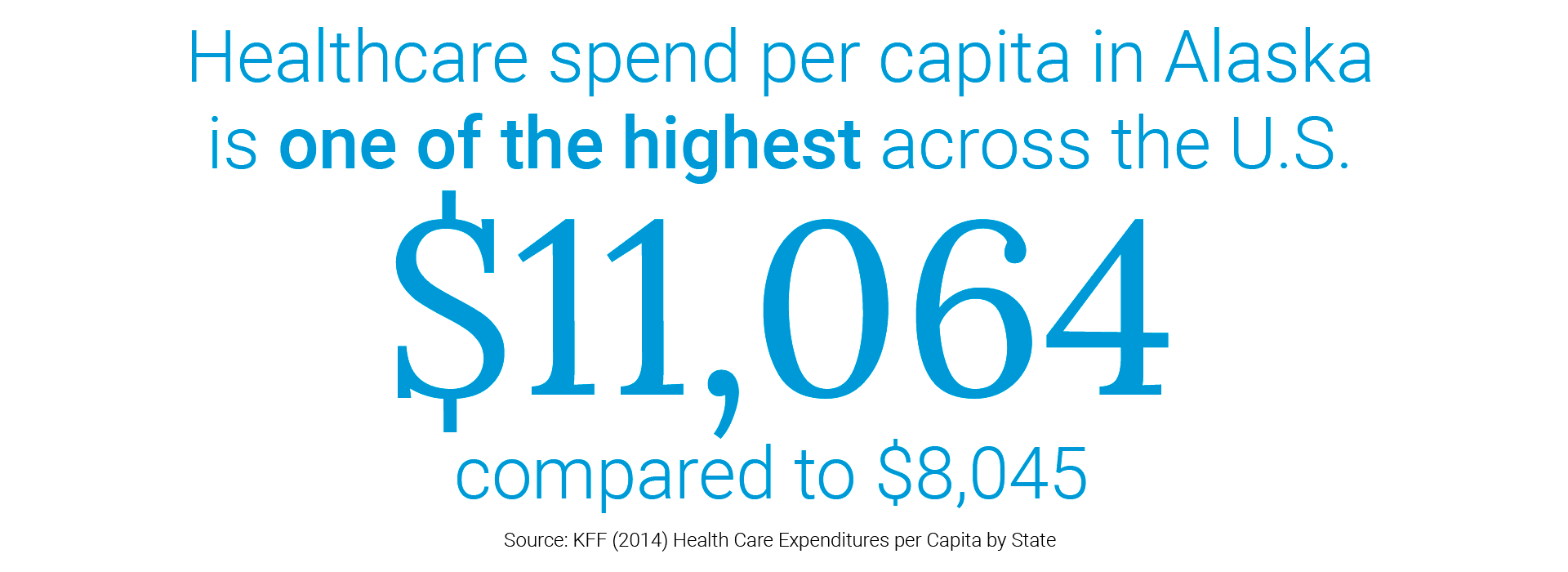

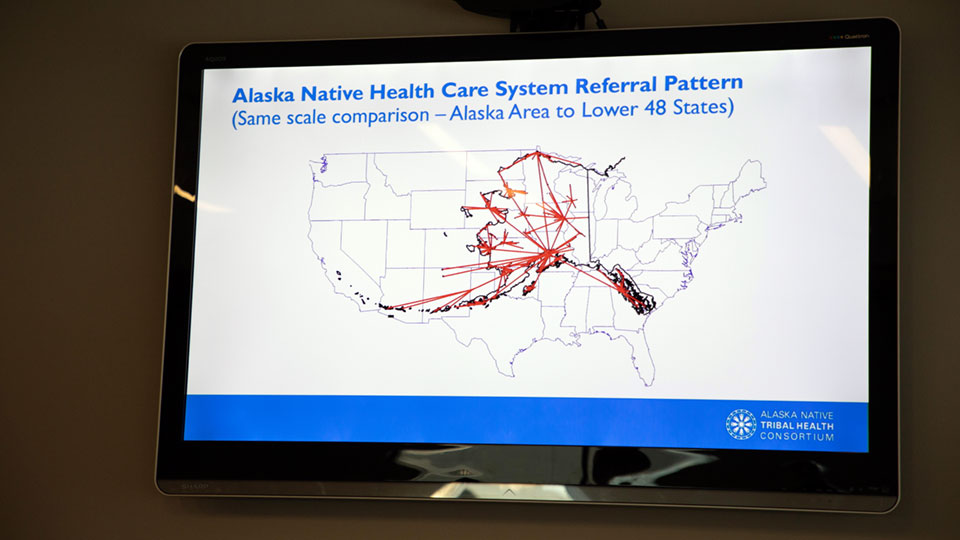

Alaska has created a hub-and-spoke-type healthcare system, with hospitals in large metropolitan areas, community health centers in smaller communities and community health clinics often staffed by one aide in villages. Patients are referred to larger facilities and providers as needed—assuming they can access those facilities by overcoming transportation hurdles. Rural healthcare is not only challenging to obtain, but expensive as well.

Big spaces, big challenges

Rural and remote Alaska and rural Washington state face many healthcare challenges.

- Rural areas do not have enough clinical workers. Those who do choose to serve rural areas experience many challenges, including overburdened patient rosters, limited training opportunities and professional isolation.

- Coordinating physical and behavioral health care is challenging and leads to less-than-optimal treatment opportunities.

- Rural area healthcare facilities, particularly hospitals, have negative operating margins, making it difficult to invest in aging infrastructure or to continue providing the outpatient care and behavioral health services patients need.

- Poverty, isolation, low health literacy rates and reluctance to get healthcare from practitioners with few ties to the community lead individuals to delay or avoid seeking care or to overuse emergency departments for non-emergencies.

Even though rural Washington state is more accessible than rural and remote Alaska, Washington residents and facilities face their challenges.

From response rates to walkways

In Lincoln County, Wash., for example, volunteer firefighters act as first responders. If they can't fully care for a patient who needs help—perhaps after a car crash—they're forced to await a medivac helicopter to evacuate the patient to a larger hospital. "Imagine how scary that is," said Janet Sowards, senior clinician at Premera Blue Cross. "You're just a volunteer and those volunteers are getting older and they're asking, 'who is going to step into those positions in the future?'"

A behavioral health center in rural Washington uses a computer system that can't communicate between the front and back end of the clinic. Another mental health clinic is inaccessible to a nearby medical facility during winter snows because there is no covered walkway. A chemical dependency facility on the Kitsap Peninsula is missing a ramp needed for wheelchair-bound veterans there to receive services. "A lot of these structures are really run down because they never got funding," Sowards said. "Nobody cares about them. When you go into them, you certainly don't feel valued as a human being. It's like we are still in a serfdom and the people with mental illnesses are outside that castle wall."

Brewster is a city in Okanogan County, Washington, United States.

Provider shortages

Some challenges seen in rural areas are common to both states, which have trouble finding and keeping the physicians, nurses and behavioral health practitioners needed to care for and treat patients. Like in the popular 1990s television show "Northern Exposure," many healthcare providers locate to rural areas to pay off student loan debt. But they don't stay long, leaving once their debt is retired. This creates a revolving door system where providers never really get to know their patients or the communities they serve, leaving patients to retell their medical history to new providers often.

In Alaska, a culture of traveling providers has emerged, where physicians and nurses are paid a bonus to locate to a remote area. Their moving expenses are covered and their salaries are higher. They stay for two or three years, then move on to their next working adventure. "They're like little Pac-Men," said Jeff Jessee, dean of the College of Medicine at the University of Alaska. "They find another bonus to gobble up. In rural Alaska, this may work great for the traveler, but it doesn't work for the local health system. It's expensive, you get people who don't know your community, your culture, and what it's like to produce healthcare in these remote areas so they don't connect well with the community and their patients and then they're gone and you have the additional expenses of paying a recruiter, another bonus, etc."

The health aide solution

Alaska is working to solve that problem statewide by training and hiring health aides, dental aides and behavioral health aides who are trained in the villages where they live to serve their own communities. The system, in effect for 20 years, works well. But finding those aides is challenging. They are often the only healthcare provider in their remote villages, on call 24x7 without local support.

Kitti Cramer, EVP and Chief Legal & Risk Officer, discusses inpatient treatments with a behavioral health aide at Elana Alexie Memorial Clinic in Napaskiak, Alaska.

Washington state doesn't have a health aide program like Alaska's. But it suffers from a similar provider shortage. "Not a lot of providers want to be isolated and live in rural areas," notes Jody Daly, chief executive of Comprehensive Healthcare, a nonprofit that provides behavioral health and substance use disorder treatment services to individuals and families in Eastern Washington. "In rural areas they have to do everything. Rural areas tend to be very concerned about burning out their healthcare workers, physicians, nurses or behavioral health people. They are isolated without a lot of peers or consultants who can encourage their work or consult with them."

Rural hospitals also struggle financially. The hospitals in Pomeroy, a town of 1,400 residents in southeast Washington, and Odessa, a town of 900 residents in central Washington, not only have trouble finding employees, but aren't large enough to succeed financially. It's not uncommon for residents to tax themselves extra to help pay the shortfalls faced by their local hospitals, said Davies, the executive director of The Northwest Rural Health Network.

In rural areas challenged by increased unemployment, accompanied by under insurance, some residents forego preventive care and instead land in the emergency room with serious medical problems, adding to hospital costs.

Populations are also older as individuals who have lived as farmers and ranchers choose to stay in their homes in their communities, rather than moving to senior care facilities in the city. "They don't want to leave there. They don't want to become urban people and live in a city apartment," Daly said. "They enjoy that solitude. Yet if they have a crisis and have to leave their community, they lose access to their support system, making recovery even harder."

Even if someone returns home with orders for in-home care from a visiting nurse or therapist, it doesn't always happen, notes Davies. "That becomes a lot harder when a person lives in a rural area. Small hospitals don't have the staff to put someone in a car and spend two hours roundtrip to serve that person because that nurse is needed on the floor."

Technology to the rescue

One growing solution that rural health providers in both states are relying on more and more is telemedicine. While not perfect, internet and broadband connections are actually quite good. Smartphone technology makes it easier for patients to connect with doctors for both physical and behavioral health; computers with high-resolution screens and cameras allow doctors to connect with colleagues and specialists in urban areas. Yet even technology isn't always enough. "Often the challenge is finding a specialist willing to do a consult," Davies said. "Those (specialists) in Spokane, for example, have a full roster of patients. It's very hard to find ones to take the time to see telehealth patients."

Transportation is another significant challenge faced by patients living in rural areas. While winter snow can clog roads in rural Washington, at least the roads exist. In Alaska, many villages are not connected by road. Rivers act as transportation routes in the summer by boat and in the winter by snow machine. But during the "breakup" and "freezeup" seasons between freeze and thaw, the rivers are inaccessible. At that time, the only way in and out is by air—assuming planes aren't grounded by bad weather.

"You're pretty much stuck where you are, which means providers in remote rural communities must be prepared for any situation," said Diane Kaplan, president and chief executive of the Rasmuson Foundation, a nonprofit that funds and promotes a better life for Alaskans.

Tax cut windfall

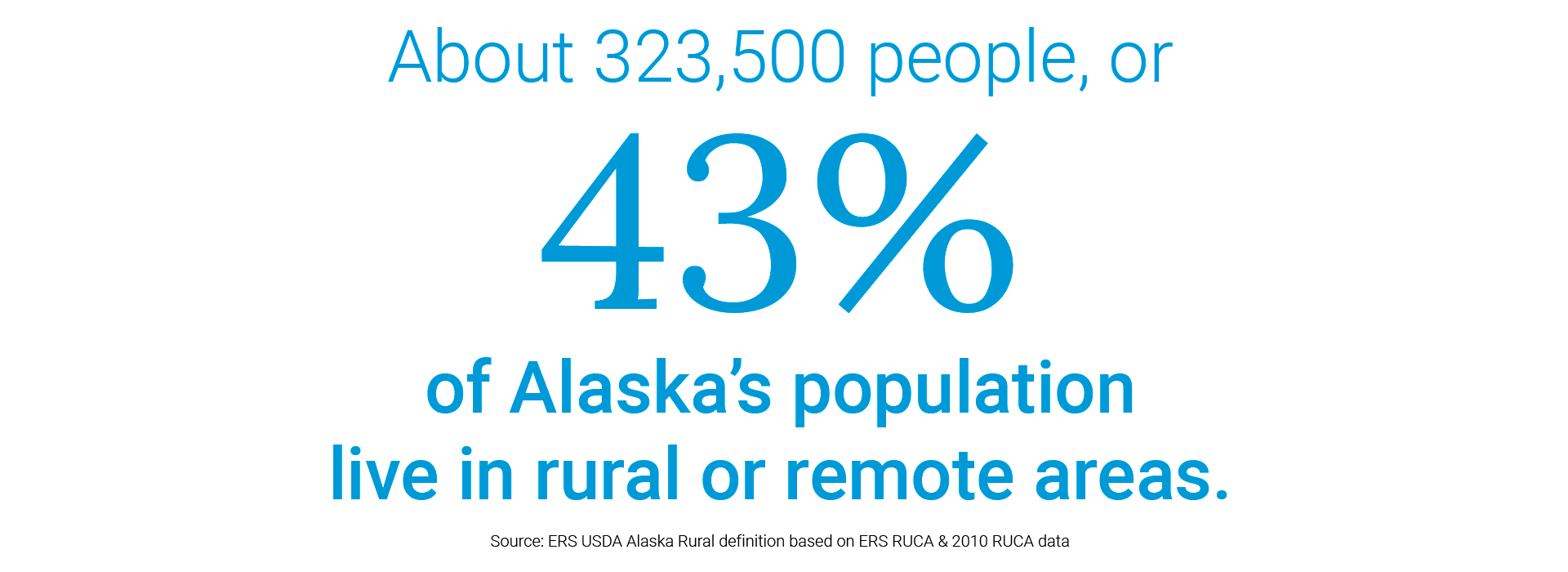

Luckily help is on the way. Premera Blue Cross is committed to addressing rural healthcare challenges in both states. In March 2018, as a result of a one-time-only refund received because of changes to the U.S. corporate tax system, Premera announced that it would invest $250 million—in part to improve access to care in rural areas of Washington and Alaska. The initiative could benefit the 1.02 million people, or 14% of Washington's population, and 323,500 people, or 42% of Alaska's population, who live in rural or remote areas.

KEY AREAS OF INVESTMENT

- Recruitment and training of physician, nurse and health aides. Rural areas experience a chronic shortage of clinicians providing primary care.

- Clinical integration of behavioral health. Primary and behavioral health clinicians often operate in silos, and many organizations are working to enhance integration to address the whole health of the patient.

- Provider-to-provider consultations. Rural clinicians often do not have the resources needed to provide specialized psychiatric and substance use treatments and would benefit from increased access to provider-to-provider consultation platforms.

- Crisis stabilization infrastructure. Individuals experiencing persistent mental health issues repeatedly end up in emergency rooms, which do not have the capacity to adequately care for them. Helping these patients remain in their communities can improve outcomes and reduce costs.

For more information, please contact Paul Hollie.

"The ultimate goal for Premera is to be able to increase the ability for people who live in these rural areas to get healthcare," Sowards said. "We really want to help accelerate the programs already in existence or those that are evidence-based. We're looking at programs that are succeeding and need more money that will help them sustain and continue the good work they're doing."